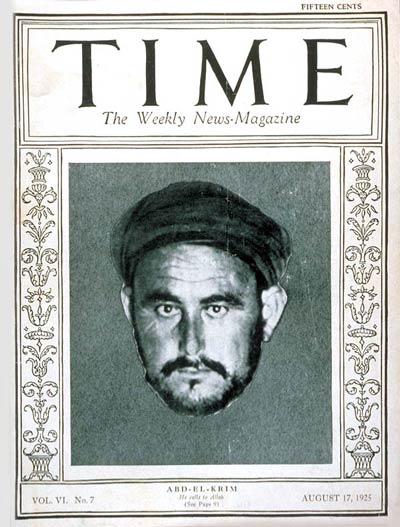

A century ago, on August 17, 1925, the face of Abd el-Krim el-Khattabi appeared on the cover of Time magazine, a global symbol of a clear and legible struggle against a foreign power. His later self-exile, from 1956 until his death, was the ultimate expression of that principled stand: even after Morocco’s formal independence, he refused to set foot in the country as long as foreign troops were still present in the region. For its inaugural essay, The New Morocco uses this anniversary to explore the phenomenon of brain drain as the modern form of self-exile. This departure of our most driven people is a profound inversion of Abd el-Krim el-Khattabi’s choice. A complex set of internal conditions drives this reversal. In understanding this impulse to depart, we find our own starting point for the journey toward new ideas.

Source: Time Magazine, August 17, 1925

Source: Time Magazine, August 17, 1925

While the economic search for opportunity and the desire for greater social freedom are powerful forces, this essay focuses on a less examined, structural cause. We will explore how our nation's very approach to change and progress has itself become a powerful stimulus for departure. The pattern of official reforms, their pace, and how their results manifest create a specific environment for our most driven citizens. In turn, the choice to leave is born from a sober, practical assessment of this environment and its inherent limitations. This is a logical conclusion reached after years of direct experience, an assessment made most often by those who feel these limits most acutely and invested in the promise of a modern, functional future. Ultimately, their departure signals a deep misalignment between the country's trajectory and the aspirations of its people.

To understand the architecture of this system, the work of the Italian thinker Antonio Gramscí offers a powerful analytical tool. He developed the concept of “transformism” to describe a specific mode of governance that ensures stability through the constant absorption and management of change. This process involves a state of perpetual reform, where emerging ideas and potential opposition leaders are gradually co-opted into the governing consensus. The effect is a powerful illusion of progress, allowing the system to appear dynamic and responsive while its core decision-making processes and established hierarchies remain unchanged. This analysis is not a critique of the desire for national stability, instead it is an examination of a particular method for achieving it. However, this historically effective method now generates significant friction in an accelerating world. A system designed for the deliberate absorption of challenges finds its gradualist rhythm overwhelmed, creating the conditions for what we can call the Gradualism Trap.

This logic of managed change creates a specific public response: “reform fatigue.” This condition is distinct from simple impatience. It is a cumulative disillusionment born from observing repetitive cycles of reform that do not yield significant structural outcomes. For many educated professionals, this pattern is a lived experience. They have witnessed successive “New Development Models” and strategic plans launched with significant public attention. While these frameworks promise decisive change, their implementation often translates into slow incremental adjustments. The process of reform itself (the reports, the committees, the dialogues…) can therefore become a substitute for the outcome of reform. After several such cycles, a predictable skepticism takes hold. The announcement of a new national plan is then met with a sense of resignation. For the individual professional, this repetitive cycle functions as a structural barrier. They conclude that the system is engineered for perpetual adjustment, not for the transformation they see as necessary. In this context, leaving is a logical response to a system whose process has become its own primary product and this preference for process over outcome has a direct, tangible consequence on the operational speed of the nation itself.

The most significant result of this culture of gradualism is a severe “institutional lag.” The defining principle of today’s world is an ever increasing velocity, where relevance is now directly linked to the capacity for rapid adaptation and even anticipatory governance. A system that prioritizes managed change, however, inevitably builds institutions that reflect this pace. The consequence is a public and private sector whose structures in administration, in business, and even in education are often hierarchical, deliberative, and risk-averse. They are designed for a past era of more linear and predictable progress. This systemic slowness places them in a state of being out of sync with the high-speed requirements of the 21st century. While many might think that this lag is temporary inefficiency to be optimized, it is in fact the direct, functional consequence of a political logic that has long valued stability over the more volatile dynamics of rapid acceleration.

The direct impact of this institutional lag on the individual is a state of chronic cognitive underutilization. Our professionals today are trained to a global standard. Their intellectual habits have been shaped by the rhythms of the modern economy: rapid iteration, agile problem-solving, and dynamic feedback loops. They are equipped to be highly responsive and adaptive. When placed within slow-moving, hierarchical institutions, they are unable to fully deploy these faculties. Their cognitive capacity is effectively throttled by a system not designed to accommodate their speed. Staying means accepting a form of intellectual atrophy and a gradual dulling of the very skills that make them competitive. This is a frustrating condition, and it makes the act of leaving a necessary search for an environment that can match, and reward, their professional velocity.

These two forces; a political logic of gradualism and the resulting institutional lag, create a self-reinforcing cycle. The system’s preference for incremental change produces institutions that operate at a slow velocity. This institutional lag creates conditions of underutilization for its most dynamic professionals, compelling many to leave. The departure of this group removes a key internal catalyst for structural transformation. With fewer voices pushing for acceleration, the state’s preference for gradualism is reinforced, ensuring the lag persists. This is a feedback loop where the strategy for stability drains the nation of the energy required for a competitive future. Each departure makes the argument for fundamental change quieter, and the argument for the status quo stronger.

The act of departure itself thus becomes a form of protest. This choice is the logical conclusion of an individual’s assessment of the system’s velocity, a verdict based on direct professional experience. It is a silent but powerful statement that the country’s current trajectory is incompatible with the demands of the future. The departure of skilled professionals is a loss of human capital and perhaps one of the most direct measure of how the Gradualism Trap is unsustainable. Each individual who leaves provides another data point demonstrating the profound gap between the nation's potential and its operational reality.

This analysis suggests a new dimension of national sovereignty. In the twenty-first century, the concept expands beyond the control of territory to include a nation’s capacity to determine its own developmental velocity. This is the ability to shape the future, rather than reacting to a future defined by others. A country that lacks this capacity risks becoming a passive actor in the global order and even at the regional level, regardless of its formal independence. The ability to compete, adapt, and anticipate has become a defining challenge of our era.