Nature abhors a vacuum, and this particular vacuum hasn’t just been filled, it’s been raped… When tradition is dismissed as old-fashioned, and the country’s second language is rejected for its colonial past, you go searching for something else. That is the predicament of Moroccan youth: a big gap in cultural education penetrated by foreign soft-power bombs. I call this colonization, not war, because the violence here is one-sided and the targets are mostly powerless. Morocco’s situation is nothing like, say, Japanese soft power in France. There, it resonated with a particular subset of the population and offered something specific and fresh without shaking the foundations. Its spread was measured, fringe for decades before it slowly became mainstream. The spread was, in that sense, healthy; “French otakus” stayed marginal and rare. This happened because French society gives its youth a solid cultural base, an education that values art, knowledge, critical thinking, and forming one’s own judgment; much the same across most Western countries.

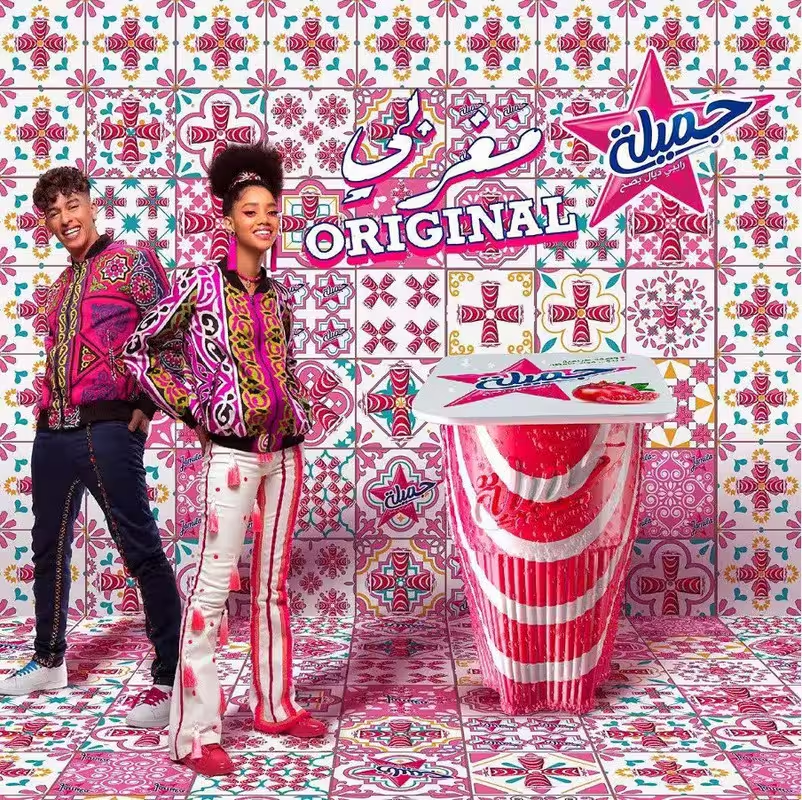

In Morocco, the dynamic is radically different. As an illustration, during a conversation with a classmate who was into American rap, he told me he had never heard of The Beatles. When I asked how, he explained that he had never really had the occasion to encounter English-speaking media until late teenagehood, and that he had mostly spent time on trending topics. Indeed, many young people do not speak English with real competence and have even less sense of the wider cultural landscape beyond their immediate surroundings. They see those surroundings as old-fashioned, and they reject the limited “high-brow” instruction they received in French, either because it is “colonial” or because they simply can’t stand the French (which, I admit, can be understandable…). Into that vacuum flow outside soft powers, mainly American, European and East Asian, met through the Internet and peers. The content is not really understood, but its popularity is obvious, so imitation begins, and then accelerates. Then comes the second-order effect: a few imitators reach the mainstream—most popular rappers are an illustration of this—and a youth with no sense of the origins or history of these styles starts copying the copy. The result is an absurdly goofy posture. Worse, some splice these derivative forms with traditional Moroccan elements, and the outcome can be a calamity: Dragon Ball characters wearing a djellaba along a Moroccan remix of the Spacetoon opening ↪, or similar crude mashups. Popular embarrassing attempts include the “Ya Wlidi” earworm or the whole Raibi Jamila campaign.

Raibi Jamila campaign

Raibi Jamila campaign

Although there are earnest efforts to produce work that is genuinely creative, original, and authentically Moroccan, they remain rare and seldom reach the mainstream. Alaa Eddine Aljem’s The Unknown Saint is a notable exception: it fuses cartoonish comedy with spirituality and reflective contemplation in a distinctly Moroccan register, channeling these through the motif of the ضريح (saint’s shrine) and the magico-spiritual beliefs it inspires. Since these genuine attempts are so rare, the majority stays exposed to the cultural radiation instead, mutating into horrendous memetic mutants. The fuel is clear: soft power bombs, addictive modes of consumption, thin cultural schooling, weak habits of critical thinking, and one that is distinctly Moroccan: strong tendency to bend to peer pressure (footnote: the fact that peer pressure is stronger in Morocco than a lot of other places could be considered, I admit, controversial, and properly arguing for this thesis is beyond the scope of this article; I will simply say that the culturally omnipresent concept of “الحشمة” is a manifestation of it, and let the reader generalize however they see fit and make their own conclusions).

How to properly address this issue remains uncertain. A sensible first step might be to grant more opportunities and resources to artists with genuinely original ideas, rather than limiting support to those producing the latest fashionable Ramadan series. Moroccan television has, of course, delivered enjoyable and noteworthy works over the years, particularly in comedy, where Hassan El Fad became something of a staple, as well as in a few non-comedic series (such as البعد الآخر, though to be honest I mostly watch for “so bad it’s good” reasons). Yet these remain sporadic efforts, generally “safe bets” crafted with the average, traditional viewer in mind. The problem worsens when producers target younger audiences, often resulting in caricatural “Yo les djeunes”–style series that lack depth and authenticity. What is needed instead are fewer constraints and more room for imagination, sincerity, and ingenuity. While even that may not be sufficient to transform the landscape entirely, it would nonetheless mark a much needed beginning.

Another, less obvious, source of hope is the corner of the Internet where interactions between an online persona and an audience snowball into a surreal narrative that grows on its own. I call these “Moroccan Memetic Myths,” or MMMs. Let me give an example of an MMM, consider the following:

He is known as Issam Sirajeddine. He makes Islamic-adjacent videos, yet has been mocked for his appearance and has answered those insults many times. Tensions then flare between those who mock him (often younger, more “liberal” types) and those who defend him (usually older, more “conservative” types). Out of this friction comes a whole corpus of lore and memes, a strange mix of the sacred and the prophane, and this mockery is done in a way which, in my eyes, is both new and authentically Moroccan, namely what is known as “trollat”.

Here is another MMM:

He is known as Cheb Larbi. He is a musician with a prolific discography, but he is known above all for his online presence and for crossing paths with other Internet MMMs, such as Ilyass El Malki. I am not a big fan of the latter, but one has to admit he coined/popularized a creative set of terms that spread like wildfire among Moroccan youth—“drb fs9ef”, “l’metaverse”, “stage lwe7ch”, “llekher”, and more. Even if these contributions veer toward the grotesque and cannot be called “art”, I would still argue they are representative of a certain authentic Moroccan zeitgeist and original in content and form. This kind of “memetic liberation” is also not specific to internet personas and can be found in facebook groups as well, particularly “trollat” groups.

We are still far from producing tear-inducing beauty, but these organic exchanges do breed originality and new shared ways of expression which, in the long run, could help foster new forms of Moroccan art.

Another example, which is not of comedic nature, but somewhat of a meme nonetheless, is this guy:

He is known as l’Morphine, a Moroccan rapper whose persona and lore place him somewhere within the realm of the MMM. Beyond that, however, he is an artist with a distinctive style—whether one appreciates his work or not—that draws on the particularities of darija for flow, rhythm, and wordplay. His music frequently incorporates Moroccan cultural elements in inventive ways: for instance, in one track, Moroccan-style weddings serve as a central theme ↪. Other figures, such as Don Bigg, Lmoutchou or 7liwa, illustrate the same trend. Despite my earlier criticisms of mainstream acts that too often imitate foreign models, rap remains one of the artistic fields where genuinely Moroccan expression has flourished most visibly. Still, the genre often feels limited in scope and, at times, repetitive. My hope is that we will see the emergence of even more original and unexpected voices in the future, not only in music but also across other media and artistic forms.

The reason I’m giving all these low-brow, underground examples is not a coincidence: once again, there are almost no “high-brow” or “mainstream” alternatives I know of. This is because, in the “official world,” Moroccan culture is reduced to Couscous, Caftan, and whatever else UNESCO might recognize as “patrimoine culturel”. By contrast, an authentically Moroccan work would reflect certain specificities of everyday behavior: the tendency to go through informal routes; a certain sense of absurdity in jokes and humor; a sense of the sacred that is at times mixed with the profane; a distinct sense of hospitality; and a way of speaking in codes (i.e. bullshitting) until a certain familiarity has been established, among others… Ironically, this last mentioned trait is also a key reason why bullshit thrives in “official art,” while more authentic expressions remain underground. Unless you have some guts (which rappers are supposed to have, given the roles they play) or are shielded by the anonymity of the internet, it is unnatural to be yourself in public as a Moroccan (again, the weight of peer pressure…), which kind of makes Moroccan culture hostile to radically new forms of expressions by default. How can we then shield ourselves from the soft power bombs ? Indeed, such an environment could hardly ever birth a Rimbaud, and even if it did, almost nobody would ever make the effort to genuinely engage with his work.

To conclude, what I wish to emphasize is that the infiltration of soft power into a country is by no means unique to Morocco. What is distinctive in Morocco’s case, however, is the resistance of its youth against long-established cultural foundations, namely traditional aesthetics and the legacy of French colonial influence. This (relatively recent) resistance has created a cultural void, which is then filled rather uncritically, owing to a lack of training, limited exposure to alternatives, and an underdeveloped sense of taste. As a result, mindless imitations proliferate rapidly. It is as though the youth had been given weapons with which to resist but, not knowing how to wield them, turned them upon one another