As of the writing of this article, roughly 78,000 km² of forests have been lost to fires in one of the worst wildfires Canada has experienced in recorded history. The total area lost is roughly the same as the entirety of Austria. An entire country burned over the course of three months, or if we want to feel it closer to home, the regions of Casablanca-Settat, Rabat-Salé-Kenitra and Fes-Meknes, combined. For the entire course of July 2025, cities like Montreal and Toronto had the worst air quality on the planet. And yet, this is not the worst wildfire Canada has experienced. That spot is held by the wildfires of 2023, where the total area burnt was 180,000 km². You might remember them as they were the wildfires that gave us the Bladerunner-like scenes over New York with the red-orange skies. Last year, similar things happened in California, and in 2019 before the COVID-19 pandemic, all eyes were on Australia with their wildfires.

Laviolette bridge in Trois-Rivières, Quebec during the wildfires of 2023

In recent years, we have come to expect wildfires in summer much like we expect rain in winter, as though they were simply part of a natural cycle. Collectively, we have started to normalize the consequences of climate change, treating them as ordinary seasonal events. In doing so, we risk overlooking both the urgency and the danger of what is unfolding, instead of questioning how we should adapt, individually and as a society, to what lies ahead.

And if you are still wondering whether wildfires, water shortages, or extreme heat waves are extraordinary disruptions that will eventually pass, I regret to inform you: they are not. This is the reality that will shape our future.

In the past two decades, we witnessed unprecedented events across Europe and the Amazon. Yet nothing compares to what the last five years alone have revealed: three of the largest wildfires in recorded history. Despite all the technological advances at our disposal, our primary recourse in the face of these disasters has been little more than anxious prayers for relief and hope for a miracle

So the question is, what causes all this? What changed during the last few years that made half of the Northern Hemisphere prone to self-combust every two or three years? The short answer to that question is very simple: Climate change.

Laviolette bridge in Trois-Rivières, Quebec during the wildfires of 2023

In recent years, we have come to expect wildfires in summer much like we expect rain in winter, as though they were simply part of a natural cycle. Collectively, we have started to normalize the consequences of climate change, treating them as ordinary seasonal events. In doing so, we risk overlooking both the urgency and the danger of what is unfolding, instead of questioning how we should adapt, individually and as a society, to what lies ahead.

And if you are still wondering whether wildfires, water shortages, or extreme heat waves are extraordinary disruptions that will eventually pass, I regret to inform you: they are not. This is the reality that will shape our future.

In the past two decades, we witnessed unprecedented events across Europe and the Amazon. Yet nothing compares to what the last five years alone have revealed: three of the largest wildfires in recorded history. Despite all the technological advances at our disposal, our primary recourse in the face of these disasters has been little more than anxious prayers for relief and hope for a miracle

So the question is, what causes all this? What changed during the last few years that made half of the Northern Hemisphere prone to self-combust every two or three years? The short answer to that question is very simple: Climate change.

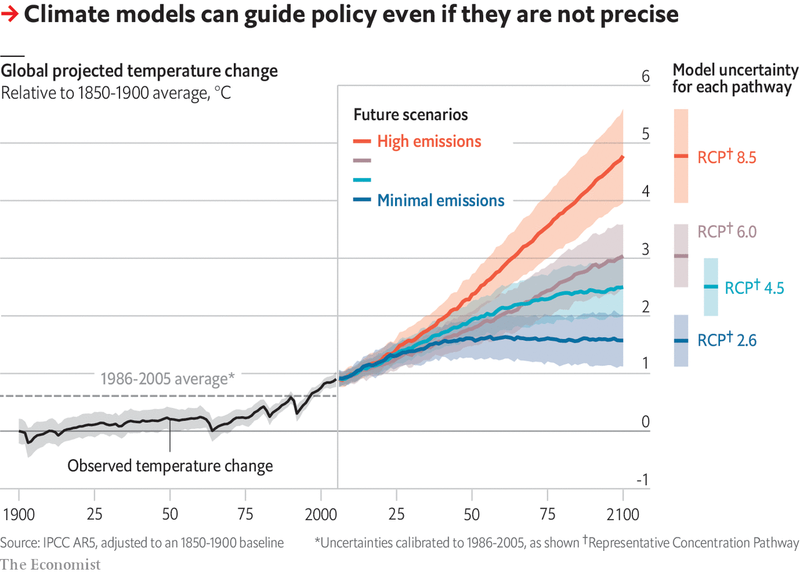

Source: The Economist ↪

Source: The Economist ↪

Even though the causes of climate change are important to examine, the subject remains complex, and some may even argue irrelevant, in the face of the urgency and the tangible impact climate change has on our societies and daily lives. While wildfires grab global headlines, we Moroccans face more immediate and visible climate threats that affect our daily lives. The most devastating impact is the water shortages that have reached emergency levels. Al Massira Dam, Morocco’s second-largest reservoir and a key water supply for farmers near Casablanca, dropped as low as 1% to 2% of its capacity in February 2024. Reality hits harder than the numbers. For a farmer, this means watching his crops wither, it means families rationing water, and entire communities forced to rely on expensive water deliveries. The agricultural heartland that feeds the nation is under an unbreakable siege. Morocco is projected to witness a decrease in water precipitation of 10-20% across the country, with a 30% decline in the Saharan region by 2100. For a country where agriculture employs nearly a third of the workforce, this translates to rural exodus, food insecurity, and economic instability that ripples through every sector.

To refresh our memories, the last time there was a mass migration within the country because of a drought, we ended up with hundreds of thousands of people in slums in practically every major city in the country; with no basic sanitation, access to clean water or public services. Those migrations transformed the entire social fabric of entire cities, and were sadly one of the main contributors of the attacks of May 2003 in Casablanca. The current drought that we are undergoing is also having visible effects. While jobs are created in other sectors like services and tourism, we are losing them in agriculture, impacting the strength of the economy overall and as a consequence all of us.

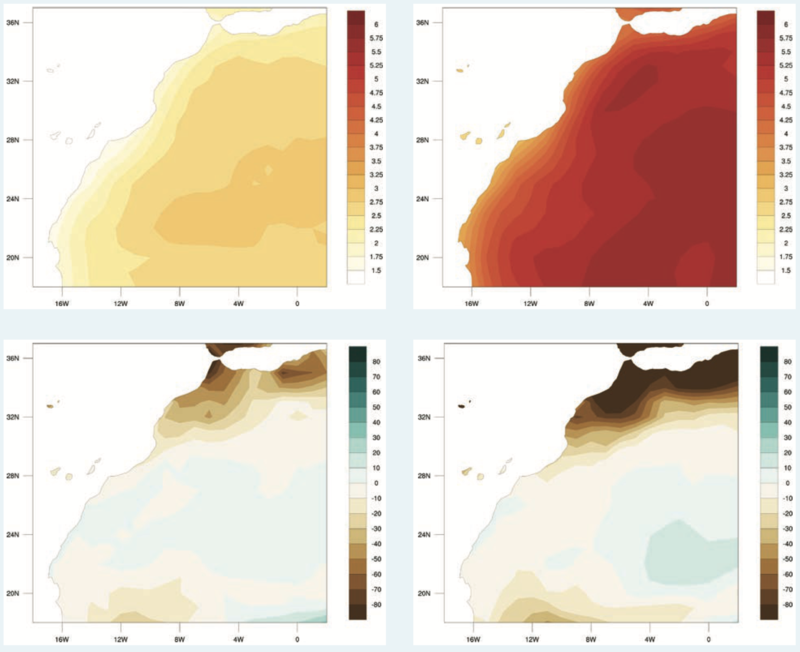

Counterintuitively, these changing patterns also mean that rain will increase in the Anti-Atlas, so we should also expect more flash flooding, and their rate and impact will be more frequent and more violent. But perhaps most visibly alarming for Moroccans are rising temperatures. The heat is also becoming unbearable. Climate models predict a dramatic rise in heat waves along the Atlantic coast, stretching from Tangier to Kenitra, with increases that could reach as high as 140 additional occurrences per year. These aren’t just uncomfortable summer days, they’re life threatening conditions that strain power grids, overwhelm hospitals, and make outdoor work dangerous. And what was an exceptionally hot summer day in our childhood will constitute an everyday reality in our near future.

How Morocco's climate is projected to change: The maps show rising heat (top) and less rain (bottom) by 2059 (left), becoming more extreme by 2099 (right). World Bank ↪

How Morocco's climate is projected to change: The maps show rising heat (top) and less rain (bottom) by 2059 (left), becoming more extreme by 2099 (right). World Bank ↪

The current climate crisis affecting Morocco didn’t come without warning. Climate scientists have been predicting these escalating impacts for decades, with research consistently highlighting Morocco’s extreme vulnerability to climate change. Research published in various international journals has consistently warned about Morocco’s exposure to increasing aridity and water stress. Many studies have indicated that there will be a decrease in precipitation values and an increase in potential evapotranspiration, leading to increased aridity risk for Morocco.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has repeatedly identified North Africa, including Morocco, as one of the world’s most climate-vulnerable regions. More specifically, projections have warned that declining precipitation and more frequent droughts would interrupt not just agriculture, but also hydropower and industrial activities that require large amounts of water. Climate projections also show that more frequent and severe droughts could occur in central and southern Morocco, exactly what we’re witnessing today. What makes these predictions particularly concerning is their accuracy. The water crisis, agricultural disruptions, and the heatwaves we’re experiencing align closely with what climate models projected would happen as greenhouse gas concentrations increased. This suggests that without significant action to reduce emissions and adapt, the worst-case scenarios outlined by researchers decades ago are unfolding exactly as predicted.

While the challenge is exceptionally hard, there are still some mandatory steps to be taken that our country and we can take to adapt to this new climate reality. And if you are wondering whether there is a defined framework to follow to avoid the consequences altogether: the answer is a clear no. However, a set of collective efforts must be taken by all of us to prevent reaching a point where progress backfires, civilizations collapse, and humanity shatters before our eyes. Consequences so heavy that our species may not survive.

While the responsibility for this crisis varies from an actor to another, the reality is that every action, as small as it may seem, will bring us a little bit towards a solution to it.

Let’s be honest about what we’re facing. The Morocco our grandparents knew, where rain came predictably, where farmers could count on their harvests, where summers were hot but manageable, that Morocco is disappearing before our eyes. The numbers don’t lie: our dams are emptying faster than they can be filled, our coastlines are retreating, and temperatures that once shocked us are becoming our new baseline. We’re not just witnessing climate change anymore; we’re living it, breathing it, rationing around it.

This isn’t a problem we can solve with a single policy change or a clever technological fix. The changes ahead will be profound and unavoidable. The economic structures that we’ve built our society around will need to be reimagined. And frankly, many of the impacts we’re already experiencing, the droughts, the heat, the coastal erosion, are locked in for decades to come, regardless of what we do now.

But here’s the thing: Moroccans have survived and adapted through centuries of challenges. We’ve weathered droughts before, we’ve rebuilt after disasters, and we’ve found ways to thrive in one of the world’s most geographically diverse and challenging environments. Our ancestors developed ingenious ways to bring water across deserts, built cities that stay cool in scorching heat, and created agricultural systems that work with, rather than against, the natural rhythms of this land. The difference now is scale and speed. We must not look at these as survival tactics, but as investments in a different kind of future. Not the future we planned for, but one we can still make livable, even sustainable. The road ahead won’t be easy, and it certainly won’t be the same as the path our parents walked. But if there’s one thing Moroccans have proven throughout history, it’s that we don’t give up when the stakes are high. The question isn’t whether we can adapt, it’s how quickly we can start, and whether we’ll do it together. Because in the end, that’s what will make the difference: not just surviving this climate crisis, but building something resilient and meaningful on the other side of it.